By Warren Dearden

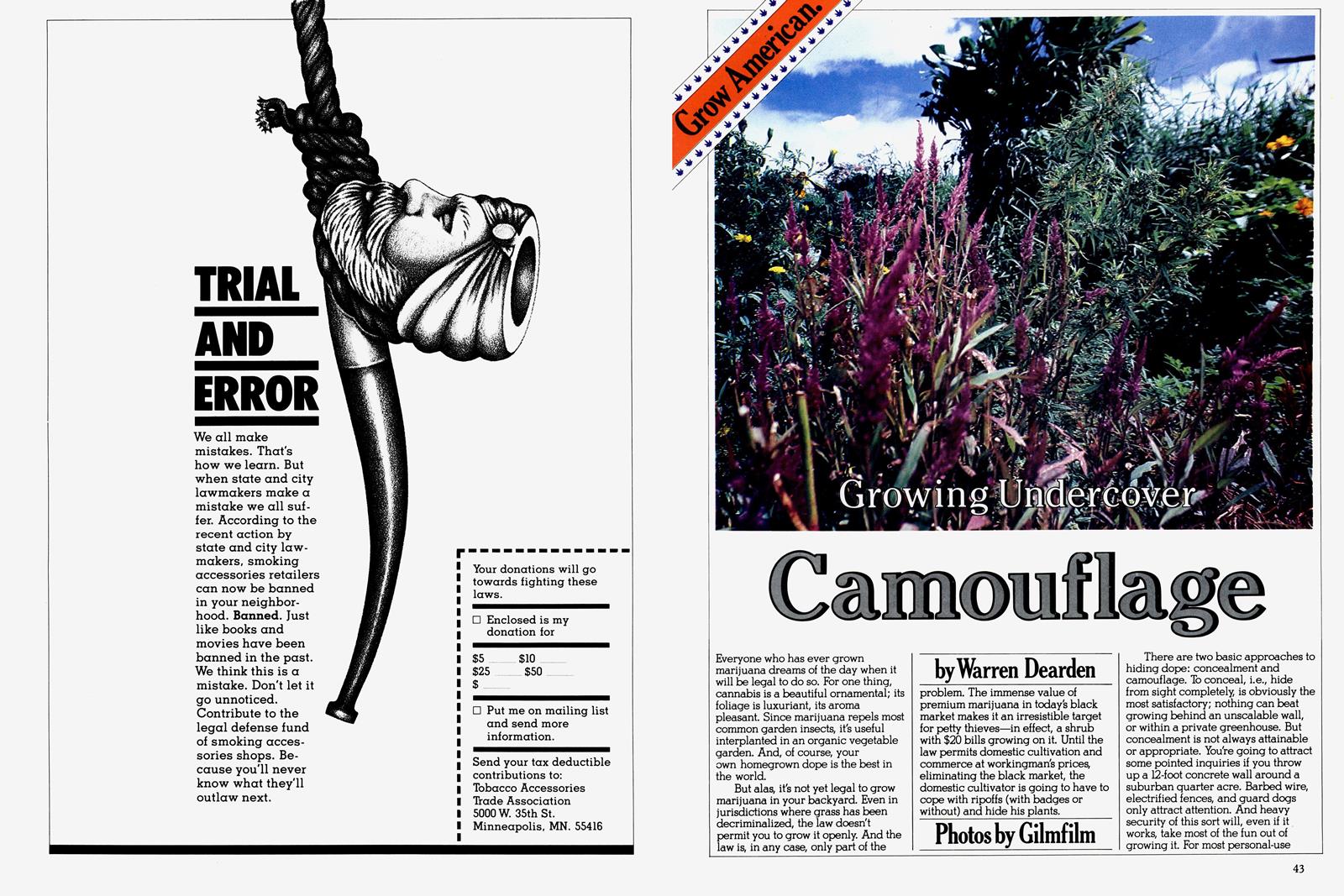

Everyone who has ever grown marijuana dreams of the day when it will be legal to do so. For one thing, cannabis is a beautiful ornamental; its foliage is luxuriant, its aroma pleasant. Since marijuana repels most common garden insects, it’s useful interplanted in an organic vegetable garden. And, of course, your own homegrown dope is the best in the world.

But alas, its not yet legal to grow marijuana in your backyard. Even in jurisdictions where grass has been decriminalized, the law doesn’t permit you to grow it openly. And the law is, in any case, only part of the problem. The immense value of premium marijuana in today’s black market makes it an irresistible target for petty thieves—in effect, a shrub with $20 bills growing on it. Until the law permits domestic cultivation and commerce at workingman’s prices, eliminating the black market, the domestic cultivator is going to have to cope with ripoffs (with badges or without) and hide his plants.

There are two basic approaches to hiding dope: concealment and camouflage. To conceal, i.e., hide from sight completely, is obviously the most satisfactory; nothing can beat growing behind an unscalable wall, or within a private greenhouse. But concealment is not always attainable or appropriate. You’re going to attract some pointed inquiries if you throw up a 12-foot concrete wall around a suburban quarter acre. Barbed wire, electrified fences, and guard dogs only attract attention. And heavy security of this sort will, even if it works, take most of the fun out of growing it. For most personal-use domestic cultivators, particularly those in decriminalized jurisdictions, camouflage is a far more practical alternative.

Tying plastic tomatoes onto a dope plant—Furry Freak Brothers-style—is pretty primitive camouflage: While it might work on the most naive beholder (your mother in town for the weekend), it wouldn’t for a moment fool a nosy cop. In the first place, a dope plant resembles a tomato plant, to the practiced eye, as a camel resembles a fireplug. Anyway, this is the completely wrong approach to camouflage—trying to make a dope plant, in isolation, look like something other than what it is. The whole point of camouflage is to make a dope plant look like nothing at all. Make it invisible.

Cannabis is most distinguishable by its stature (six to twelve feet) and its large, serrated, seven-fingered primary leaves. It will obviously be far less conspicuous if it is pruned once or twice before it buds and kept to a height of four or five feet. Topped ruthlessly, trained to a height of two or three feet, it loses its conical shape entirely, making it nearly invisible to the distant observer. But topping doesn’t really do the trick when the observer is able to approach more closely, because those primary leaves are of a distinctive size, shape and color—a red, white and blue flag to the practiced eye. Leaf trimming is the sine qua non of camouflage.

The question is how much to trim, and when. A dope plant, like any plant, depends upon its leaves for the photosynthesis that powers its whole biology. Trimming it too rigorously will stunt and weaken it. But there is apparently a fairly large margin for error in this matter, for the question of whether or not to trim leaves has been a matter of hot and heavy debate among Maui wowie growers for the better part of a decade, and the subject of continuous experiments. Partisans on either side include the best and most experienced growers, whose dope is equally stoney, suggesting that it makes little difference or none in terms of the final product, and that you can trim leaves with relative impunity, according to camouflage criteria. The best rule of thumb is to trim primary leaves only after the secondary leaves have burst from their buds and begun to spread, and to trim secondary leaves only when they become so dense or large as to resemble primaries.

Topping and trimming a dope plant doesn’t make it disappear, of course, any more than tying on plastic tomatoes disguises it. It must have an ambience to disappear into: a garden, a weedy field or a glade full of similar vegetation, where it doesn’t look out of place. A family vegetable flower garden is the ideal ambience for a camouflaged marijuana plant, especially a large, disorderly, overgrown garden. Best of all is a garden on a farm, where no nosy neighbors or cops come snooping. Minimally, a garden in a place where gardens (or oneself) are not so unusual as to attract unwanted scrutiny. A garden with an ordinary inconspicuous livestock fence, and an unlocked gate—to which entry can be controlled, if not entirely prohibited. An ordinary family-sized organic garden, with a family-sized number of marijuana plants scattered through it, in twos and threes.

Vegetables are, obviously, crucial to the ambience of a vegetable garden, an alibi for your long sweaty hours of stoop labor. And, though no vegetable resembles marijuana closely enough to make it disappear, there are several that by their stature and luxuriance contribute to ambience, and can be used to block off sight lines. Corn is wonderful this way, growing if not taller than an elephant’s eye, taller than a man’s. Through a patch of it several rows deep, one can see very little beyond. And, perhaps the most recognizable of all vegetable plants, it’s great for ambience: As nothing else, it makes a garden look like a vegetable garden.

Nearly as good are sunflowers and pole beans. Sunflowers have leaves the size of dinner plates and attain a height of seven or eight feet. Pole beans will clothe a ten-foot-high trellis with foliage as opaque as a brick wall.

But sunflowers and beans aren’t quite subtle enough. Because they are so tall and make such excellent concealment, they invite the suspicions of the suspicious. So they are useful mainly in secondary uses, blocking off sightlines rather than in close proximity to the target plant, and as decoys, giving the suspicious something to look behind.

More subtle are the tomato, the sweet pea, the eggplant, the okra, and the pepper, plants that stand up in the garden to a height of three or four feet. Too short to block off any long sightlines, and thus appearing to conceal nothing, these waist-high vegetables are handy for screening bush-shaped, waist-high dope plants, or as part of a thicket surrounding a taller dope plant. More subtle still are the carrot and the beet, the lettuce and the melon, growing ankle high. They’re useful in the way they can control ground space, directing the feet of a trespassing beholder (around a lettuce bed rather than through it) and useful for the way they reflect light, for the diversity and confusion they lend.

The best camouflage for marijuana is among flowers, a few kinds especially. Marigolds are very good: Their foliage from a distance somewhat resembles that of a flowering marijuana plant, and their big brilliant orange and yellow flowers just dazzle the eye. And marigolds, as a sort of bonus, will imbue the buds of dope plants grown beside them with a taste of their delicious aroma. Certain kinds of ornamental sunflowers are useful, particularly a branching, smaller-flowered kind called Tithonia. It grows five or six feet tall, has luxuriant foliage, and sports profuse, dazzling vermilion flowers. Scabiosa is handy, with its weedy foliage, five-foot stature, and bright flowers in a variety of colors. Blue salvias are excellent camouflage, although, like marigolds, they don’t grow as tall as you’d like. And a few others, like hollyhocks and regular sunflowers, are useful because they’re tall, bright and distracting. But the best camouflage flower, the marijuana grower’s mainstay, is a flower called, appropriately enough, cosmos.

There are two kinds of cosmos, so different that their synonymy is puzzling. The kind called Sensation, with purple and lavender flowers shading into red and white, and ferny foliage, grows as tall as five feet. Its height, profuse flowers and distinctive foliage make it nearly as useful for primary (close-in) camouflage as tithonia. But it is the other kind of cosmos, called Bright Lights, with flowers of orange, yellow and red, and trilobate leaves, that really turns the trick. It doesn’t grow as tall as marijuana—practically nothing does—but it reaches a height of five feet, and its branching habit is nearly identical. Its foliage, while not quite the same color as marijuana, or similar enough to be confusing on close inspection, hangs from the branches the same way, and flutters similarly in the breeze, showing the beholder a very similar pattern of light and shadow. And its flowers live up to the name Bright Lights, growing out of the foliage on long graceful stems, bursting brilliant orange by the hundreds, dancing in the breeze. A marijuana plant, trimmed to an appropriate height and shed of its primary leaves, disappears utterly in a clump of flowering cosmos plants, invisible from only a couple of yards away in full daylight.

Effective as it is, however, a clump of cosmos is very elementary camouflage. It only works on someone who isn’t looking for it: To a ripoff who knows the trick, a clump of cosmos is a dead giveaway. That’s where the other flowers come in, as camouflage for both the marijuana and the telltale cosmos. A marijuana plant screened by a couple of cosmos, a couple of marigolds, a tithonia, a pea vine, a salvia and a tomato is nearly as invisible as among a halfdozen cosmos. And that screen itself becomes invisible amid a particolored profusion of flowers and foliage, vegetables, herbs, and ornamentals of the widest possible variety, consistent with the ambience of the whole garden. Here, where the camouflage camouflages the camouflage, is where the eye of the artist meets its most subtle challenge (“Is it good enough? Is it finished?”).

Vegetables, herbs and flowers are of course only the camouflagist’s palette, and understanding the usefulness of each, being able to see each as a living light sculpture, is only part of camouflage technique. Equally, if not more, important is an understanding of (or an eye for) the fundamental principles of composition and perspective. An exceptionally tall plant (a sunflower) will make all the plants in its vicinity look smaller than they are. A gazing human eye can be dazzled and distracted by brilliant, dancing flowers. A strong vertical line can steer the eye upward, a powerful foreground element can hold it. Perception of color and shape can be dramatically altered by the juxtaposition of different colors and shapes; there are some huge, exploitable loopholes in the laws of perspective. Distortion of the beholder’s perspective and misleading tricks of composition are the camouflagist’s stock in trade.

Camouflage is no protection against a systematic, close inspection in the full light of day, so if you’re worried about the police showing up with a search warrant and a German shepherd, forget it. But each of the camouflagist’s other major enemies, the neighborhood kids snooping by moonlight, a police officer conducting a hasty unwarranted search, a nosy stranger peeking over the fence, is working under a handicap that the camouflagist can exploit and enhance.

The stranger peeking over the fence is a good example. Trying to remain inconspicuous, he or she will approach your garden by the route that offers the best concealment (or the best alibi), and peek over your fence at the most promising spot: If he can see the whole garden from this spot, and can see nothing, he probably won’t bother to take a second peek. Since his route of approach can usually be narrowed down to a couple of choices, the “most promising spot” that he chooses to peek into your garden can just as easily be predicted and manipulated by the design of the fence and the landscaping outside the fence. Being able to predict his point of view so accurately makes it possible to camouflage against him with considerable precision.

The neighborhood kids snooping by moonlight are even easier to trick, working under several handicaps. They can see very little, in the first place: The full moon provides only one three-hundredth (1/300) of the light of the sun—enough to locate a prescouted plant perhaps, but not enough to scout out a camouflaged one; a flashlight, if they dared use one, would cast so many shadows it would make the camouflage more effective. And being teenagers, they think everybody is as dumb as them. They will come snooping, most likely, for a dozen marijuana plants all in a row, approaching by a pretty predictable route. Entering your garden through the gate, or climbing the fence at the easiest spot (wherever you want them to), they will follow a predictable pattern in their search. They will search the spots that seem most likely to them—amid the corn, behind the lima beans, in the lee of your toolshed—and pull up an innocent young marigold as like as not. Their search will probably be a brief, perfunctory one in any circumstances. If they do find a plant, they will take it and run like hell, leaving your others alone.

A police officer conducting a hasty, unwarranted search (an overzealous narc following up a tip that a judge won’t give him a warrant for) is a camouflagist’s worst enemy. He works in the full light of day, as the neighborhood kids will usually not dare, and he has a damned good picture of what he’s looking for. He’s bolder and more deliberate than the ordinary sneak thief, confident that his badge (not to mention his gun) will protect him from pitchfork-wielding hippies. His handicap (having to give up his search if you actually catch him at it and ask him to) is a handicap only relative to a police officer with a warrant (who will double his search if you ask him to quit, and if all else fails discover some evidence in his pocket).

But his handicap, such as it is, can be exploited. If a garden is overlooked by a house or two, and protected by a barking watchdog, he will worry more about being interrupted (and the indignity of having a citizen tell him to beat it) than about being systematic. Since he is, generally speaking, a law-abiding person who doesn’t like to go wantonly trampling through people’s flower beds, a constipated person who’s worried about getting shit on his shiny brown shoes, he will usually keep to the paths you have laid out in your garden and can be discouraged from searching a whole section of a garden by a well-placed, really ripe compost heap. And ambience will throw him off stride more than anything: If a garden looks more like a respectable Republican vegetable and flower garden than he expects a dope garden to look, he’ll begin to worry that he’s gotten another bum tip. Since he is entering the garden by a predictable route, and following a somewhat predictable route in his hasty search, it is possible to predict somewhat his points of view, and to manipulate by camouflage what he will see from them. Just hope he hasn’t read this article.

The question of whether camouflage is going to be the answer to the problems of a particular domestic cultivator is one that must properly be considered in the context of his particular legal climate: whether the local police conduct unwarranted searches, whether the local judges will convict on the basis of illegally gathered evidence, whether (and how much) dope in your garden can get you locked up. For camouflage is truly more of an art than a criminal technique: the province of poets, philosophers and dilettantes where the law only slaps one’s hands, but far too imprecise to dabble in where the law flings 20-year sentences at thought criminals. In jurisdictions where it is feasible, in neighborhoods where the police (or the neighbors) aren’t aggressively nosy, camouflage can be the answer to the ordinary dope fiend’s prayers. To the ordinary starving artist, it offers, besides the satisfaction of a neat trick, something to keep his muse stoned.

This article appears in the March 1981 issue of High Times. Subscribe here.

Read the full article here