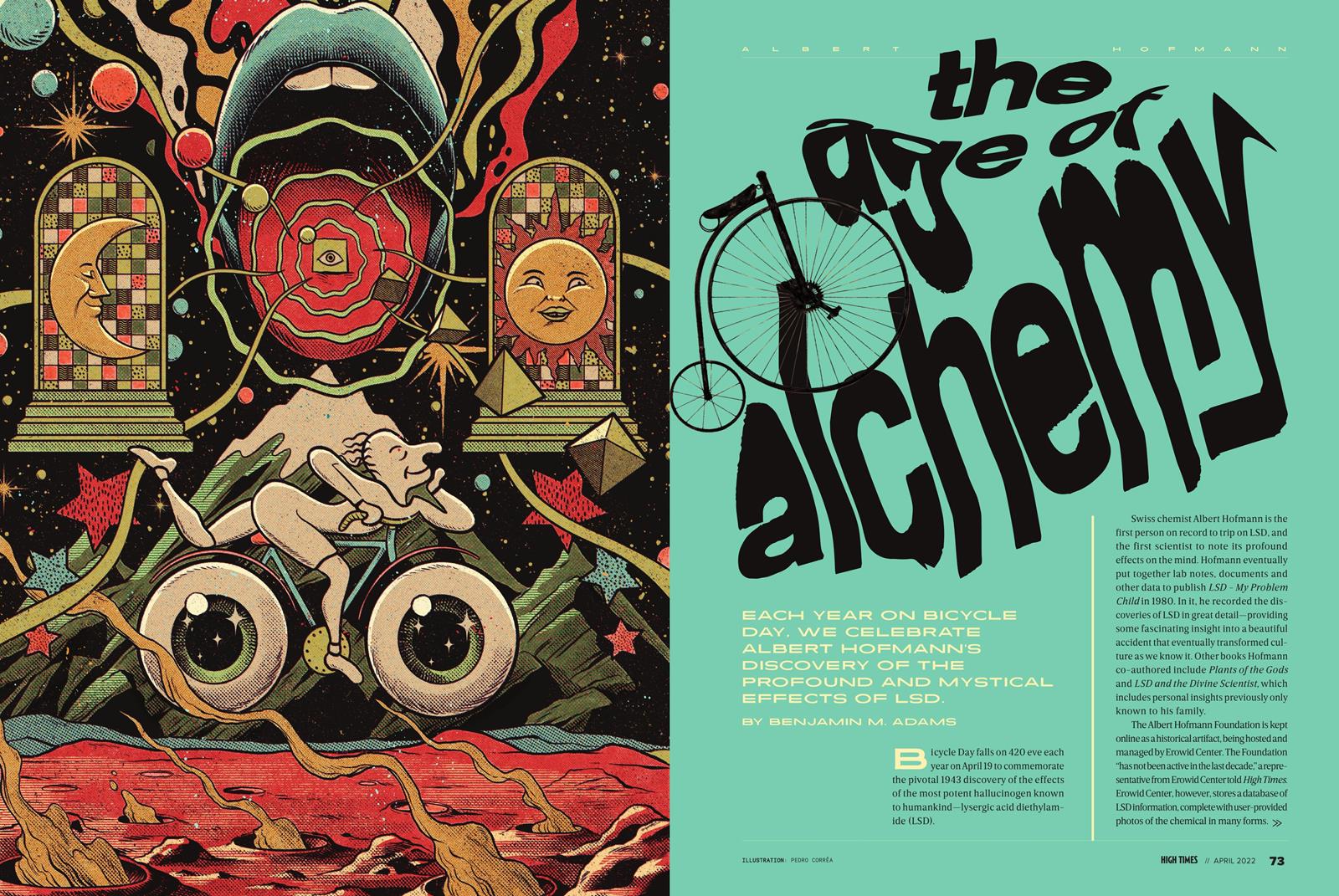

Bicycle Day falls on 420 eve each year on April 19 to commemorate the pivotal 1943 discovery of the effects of the most potent hallucinogen known to humankind—lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann is the first person on record to trip on LSD, and the first scientist to note its profound effects on the mind. Hofmann eventually put together lab notes, documents and other data to publish LSD – My Problem Child in 1980. In it, he recorded the discoveries of LSD in great detail—providing some fascinating insight into a beautiful accident that eventually transformed culture as we know it. Other books Hofmann co-authored include Plants of the Gods and LSD and the Divine Scientist, which includes personal insights previously only known to his family.

The Albert Hofmann Foundation is kept online as a historical artifact, being hosted and managed by Erowid Center. The Foundation “has not been active in the last decade,” a representative from Erowid Center told High Times. Erowid Center, however, stores a database of LSD information, complete with user-provided photos of the chemical in many forms.

Originally, LSD was available from researchers as a tablet, but today, LSD is found in tiny stamps of blotter paper, geltabs, microdots or in liquid form. Its mystical effects on the mind are difficult to explain to someone else.

“Albert Hofmann himself was a mystic,” Founder and CEO of Third Wave, Paul F. Austin told High Times. “So, he had that first Bicycle Day experience in 1943, but it wasn’t just that first experience—he continued to work with it and gave it to close colleagues at his research institute. What they experienced, over the next four to five years, in 1943-1948, was significant in terms of the breakthroughs that they had.” Twenty years later, Hofmann’s focus shifted to psilocybin and other psychedelics.

Third Wave provides well-researched, high-quality information specific to the classic psychedelics with an emphasis on microdosing. It was thanks to researchers like Hofmann that the enormous potential for psychedelic-assisted therapies was revealed.

Once the effects were known, government-funded LSD studies and experiments were everywhere, with involvement from entities such as the FDA, CIA and British government. Actor Cary Grant, for instance, dropped acid an estimated 100 times, spanning the years of 1958-1961, supplied by Dr Mortimer Hartman at the Psychiatric Institute of Beverly Hills in California. To Grant and other volunteers, lighter psychedelics such as cannabis might have seemed like a cup of tea compared to LSD.

Some people view LSD as the prime catalyst of 1960s counterculture—as much of a game-changer as cannabis. LSD couldn’t be confined to research and government-led science projects, creeping into the general consciousness. By 1966, “Turn on, tune in, drop out” was the catchphrase popularized by LSD gurus like Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg or Ken Kesey, while scores of bands such as Grateful Dead and The Beatles were inevitably inspired by the mystical chemical.

The US banned possession of LSD on October 24, 1968 while the FDA continued LSD research on volunteers until 1980.

Experts helped High Times piece together the story of Hofmann’s LSD breakthrough, and how modern-day coaches can help people navigate safely though psychedelic experiences.

Early Research

In 1929, Hofmann left the University of Zurich to work at Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, with the specific goal of developing new pharmaceuticals based on active plants and fungi. The pharmaceutical department was small, with a handful of researchers on the team with doctorates.

By 1938, Hofmann was attempting to develop a new analeptic—a drug used to treat respiratory and circulatory issues. Analeptics are used most often as a restorative drug to help people awaken and recover from anesthesia.

Hofmann’s team elected to study plant and fungi compounds of “recognized value” including woolly foxglove (Digitalis lanata), Mediterranean squill (Scilla maritima), and ergot of rye (Claviceps purpurea or Secale cornutum). All three are poisonous in natural form. At first, the team thought Mediterranean squill would be most interesting, because it contains cardioactive glycosides, which are beneficial for the heart. Mediterranean squill is a plant used in Ancient Egyptian medicine for various conditions.

Woolly foxglove contains a natural steroid, which also seemed useful. Ergot, on the other hand, is a poisonous fungus that grows into tiny black fingers on crops of rye. It’s been used occasionally to stop bleeding, but it is mostly viewed as a poisonous fungus. It was blamed in the Middle Ages for St. Anthony’s Fire—or ergotism, which can cause the loss of limbs or death centuries ago. That’s why the poisonous elements of ergot have to be processed and separated. Hofmann was interested in its properties as an ecbolic—a medicament to precipitate childbirth.

Neither Hofmann nor anyone else knew about its psychedelic properties. Hofmann extracted LSD-25 from a sample of ergot on November 16, 1938. To do this, he chemically linked two components of ergobasine, lysergic acid and propanolamine, using a relatively complex lab process. Lysergic acid diethylamide, abbreviated LSD-25, was the 25th substance that Hofmann synthesized from ergot, and at first, it was “relatively uninteresting.”

Hofmann’s new “analeptic” just wasn’t panning out how he planned. When he administered it to lab animals, they just sat there for hours—so Hoffman set the LSD aside for five years and forgot about it. On April 16,1943, Hofmann took one last stab, synthesizing a new batch of LSD from ergot. During synthesis, a droplet of acid touched his skin.

Founded in 1986 by Rick Doblin, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization specializing in research and education covering the medical, legal and cultural shifts of “the careful uses of psychedelics and marijuana for mental and spiritual healing.”

Since 1986, MAPS has distributed over $20 million to fund psychedelics and medical cannabis research and education. Doblin’s work was covered in former Washington Post Magazine editor Tom Shroder’s book Acid Test: LSD, Ecstasy, and the Power to Heal.

“Back in 1938, Albert first synthesized LSD, but he had no idea about the potential of LSD in therapy,” says MAPS Founder and Executive Director Rick Doblin. “Sandoz gave it to animals and found nothing of interest. Albert didn’t learn about the psychedelic properties of LSD until five years later in 1943 when he re-synthesized it on April 16, 1943, and inadvertently absorbed some and had an unusual experience […]”

Doblin received his master’s and PhD in public policy from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, and was in the first group to be certified by Dr. Stanislav Grof as a Holotropic Breathwork practitioner. One of Doblin’s projects is working to form a database for Albert Hofmann Foundation’s LSD and Psilocybin Library. Doblin asked, “How Can We Use Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy To Treat Trauma?” including LSD in a 2019 TED Talk that was shared in 2021 by NPR.

The First Trip

Within an hour of first contact, Hofmann experienced an intense rush of profound inner feelings and geometric hallucinations of color. He found it difficult to put his experience into words. The five senses just didn’t really seem to be sufficient to explain its powers.

He sent a report to Professor Stoll about his experiences. He was overcome by a “remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness.” He made it home and sank into a dreamlike state, with eyes closed. He perceived an uninterrupted stream of “fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.” After about two hours more, the effects faded away.

Hofmann couldn’t stop thinking about it, as evident in his notes. Three days later, on April 19, 1943, Hofmann set out to experience LSD intentionally. He guessed that 250pg (micrograms) would be a good starting point, and he swallowed a drop of it at 4:20 pm, according to his meticulous records. Hofmann poured the LSD into 10cc of water to dilute it, and drank it.

Within minutes, Hofmann realized with horror that he had screwed up: the rush of hallucinations and effects was way too strong and getting stronger.

He was only able to write the last words “with great effort.” It was already clear to Hofmann that LSD had been the culprit for the remarkable experience the previous Friday, which altered perceptions, only much more intensely. He struggled to speak intelligibly, asking his laboratory assistant to escort him home and she was aware of his experiment. They were forced to travel by bicycle, as no automobiles were available because of wartime restrictions. On the way home, Hofmann’s condition worsened.

Hofmann called his assistant to help him ride the bike home. But Hofmann explained that his assistant transformed into “a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.” Hofmann explains a demonic transformation in himself as well. His ego was completely dissolved, and he felt as though a demon or something else was controlling his body. Hofmann chugged two liters of milk—thinking that it would reduce the effects of LSD. Eventually however, Hofmann’s bad trip gave way to a euphoric high with pleasant visions.

Hofmann’s wife had heard that he was going through some sort of breakdown, and rushed to Basel from Lucerne to check on him. By the time she arrived in Basel, the effects had worn down, and Hofmann could not stop talking about this experience. His doctor came over to check his vitals, and found nothing to be concerned about, other than his dilated eyes.

He was shocked how “real” the new reality under LSD seemed compared to normal consciousness. He said he felt as though LSD itself summoned him to discover it.

“Albert’s experience on April 19 was frightening—but it also had spiritual elements,” said Doblin. “He and others at Sandoz initially thought LSD could be good for training therapists and psychiatrists so that they could get an experiential perspective on what some of their mentally ill patients were experiencing. One of the first words for this class of drugs was ‘psychotomimetic’ meaning that the experience was similar to psychosis. It was only over time as more researchers tried it that the therapeutic and spiritual potential became better understood and it was clearer that much more was going on than just mimicking psychosis.”

Hofmann wrote that he was convinced LSD would be used in pharmacology, neurology and “especially in psychiatry.” He never envisioned that LSD would be taken over by hippies and musical artists.

“So, Hofmann really came to the conclusion [that LSD has potential in pharmacology] [not only] based on his own experiences, but because he slowly started to ship it out for free,” Austin said. “And those were the reports that kept coming back: ‘Wow. We’ve never encountered something like this before.’ As helpful as this has been for dealing with mental issues.”

LSD in Pharmacology

Austin explained that psychedelics were panned as useless in previous eras. “Before acid and mushrooms were called psychedelics, they were called psychotomimetics, because they mimicked what people [at first] thought was a state of psychosis. Through that mimicking of a state of psychosis—which is this classic mystical experience—what a shaman might facilitate—that minds were open to this conditional love.”

Austin went on to say that at research facilities including locations at Johns Hopkins, researchers are learning that dealing with unconditional love is why psychedelics precipitate healing from depression, addiction, anxiety and so on.

But people need to be aware of the sheer power they are dealing with, especially when it comes to LSD. “In terms of all the well-known psychedelics, it’s the most potent at 10 micrograms. 100 micrograms is still a tiny amount, which is a full-blown dose.”

Dose-for-dose—LSD tops all other hallucinogens in potency, as other hallucinogens require a much larger dose.

“That’s why the ’60s went so sideways,” said Austin. “It was because acid was such a potent psychedelic, and you had figures like Timothy Leary […] and Ken Kesey, who just passed it out far and wide to anyone and everyone. Even though it was a tiny amount, it was blowing people out of their minds. It’s a major reason why you don’t see as much research on it versus other psychedelics like psilocybin.”

Hofmann passed away in Switzerland on April 29, 2008. One of the ways Hofmann’s chemicals are kept alive is through companies such as Third Wave. Psychedelic experiences are not to be trifled with, so there is a lot of preparation and know-how required.

“We do what I would call education and training,” said Austin. “So, a lot of my focus is on history. I recognize a lot of the mistakes that were committed in the 1950s and ’60s, particularly in the ’60s. We had—even in the ’50s and ’60s—over 1,000 clinical papers published on the efficacy of LSD. So, we had all the research—but when psychedelics made the leap from clinical studies to culture, things went sideways.”

Austin continued, “We focus instead on microdosing and the clinical benefits of microdosing, because it helps. Even at very, very low doses, psychedelics can be potent. And so we have a course on how to work with microdosing. We do a training program for coaches, so if you’re a coach, or if you want to be a coach in the psychedelic space, we train on what we can ‘the skill of psychedelics’ to be able to help other people as well.”

Third Wave just rolled out a mushroom grow kit, with a course on how to grow your own mushrooms, given the current momentum around psychedelics. (Psilocybin is still illegal almost everywhere.) Third Wave works within a legal framework to make these substances a bit more accessible.

This article was originally published in the April 2022 issue of High Times Magazine.

Read the full article here