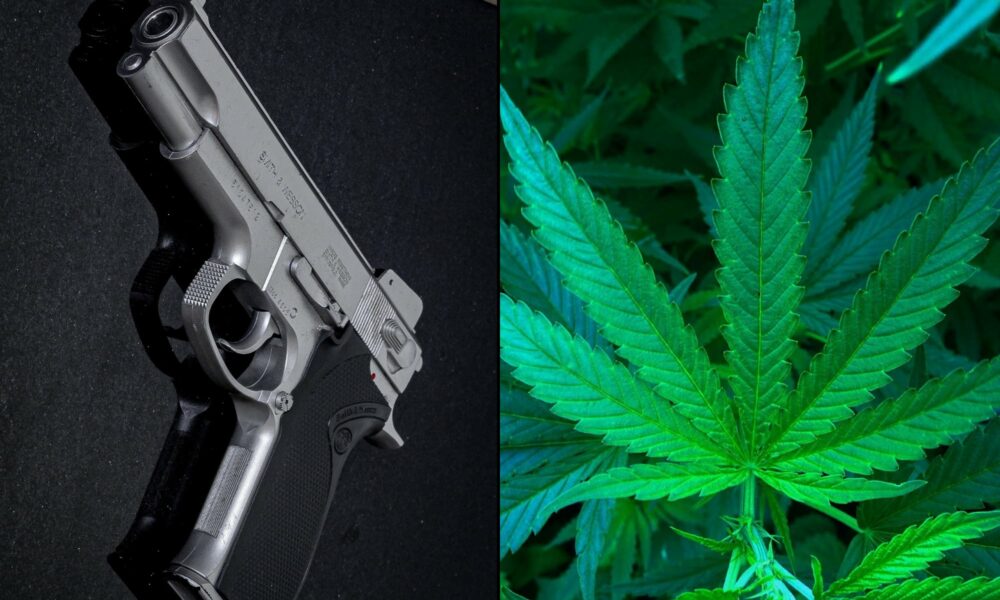

The Supreme Court on Monday heard the case of a defendant seeking to reduce his criminal penalty for firearm possession as the result of the federal government’s legalization of hemp in 2018.

At issue are the boundaries of the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA), a 1984 law that imposes penalties on gun possession for people with past violent felonies or serious drug offenses.

Initially the law imposes a 10-year maximum penalty for having a firearm, but after three offenses, a 15-year mandatory minimum sentence kicks in. Like other three-strikes laws, the act was intended to dissuade recidivism by ratcheting up criminal penalties for repeat offenses.

The case before the Supreme Court, Brown v. U.S., which is consolidated with the case of a separate petitioner, centers on what qualifies as a relevant drug charge for ACCA’s purposes given that laws around controlled substances are quickly changing and, in some cases, creating conflicts between state and the federal government.

Notably the ACCA itself doesn’t include a list of substances that qualify under the statute, instead relying on other statutes to determine whether a conviction is relevant.

“We think the cross-reference to an external body of law that is dynamic is critical here,” Austin Raynor, a Justice Department lawyer, told the court on behalf of the federal government. “In our view, the cross-reference raises a temporal question. When Congress chooses to reference an external body of law, that raises the question, which version of that body of law is Congress intending to reference?”

The court, in its description of the issue presented in the case, highlighted what’s at stake for criminal defendants, noting the distinction “dictates the difference between serving a 10-year maximum or 15-year minimum.”

Justin Brown is one of two petitioners in the consolidated case. He faces a 15-year sentence for gun possession that he asserts was the result of a Pennsylvania court wrongly using his past marijuana offenses to sentence him under ACCA because the federal government legalized hemp through the 2018 Farm Bill. Brown was sentenced in 2021, after the law changed.

“We submit that the sentencing court should use the schedules that are current at the time of sentencing,” said Brown’s attorney, Jeffrey T. Green. “This Court has said that the ordinary practice is to apply current law, including at sentencing.”

“There’s no reason to deviate from that ordinary practice here,” Green continued. “The goal of the ACCA is to incapacitate only the most serious offenders… To do otherwise, as the government suggests, would be to ignore entirely Congress’s choice to change those drug schedules with the 2018 Farm Bill.”

“Is it true that acceptance of your argument would mean that no marijuana conviction prior to 2018 would count as an ACCA predicate,” asked Justice Samuel Alito.

“No,” Green replied, “because there would have to be a match between the state and federal.”

Some conservatives on the court seemed to side with the idea that the laws in place at the time of the original drug offenses are what courts should look at, while more liberal members suggested courts should look at drug laws at the time of the firearm possession conviction.

“When you’re cross-referencing something you’re taking everything with it,” said Justice Sonia Sotomayor. “You’re picking and choosing and now saying, ‘I’m only going to take a piece of it, not all of it.’”

She seemed inclined to side with Brown, whose attorney argued that courts should look to laws and regulations on the books at the time of the firearm offense itself.

A conservative justice, Neil Gorsuch, also seemed sympathetic to Brown’s argument.

“You’re going to have to go look at old sentencing guidelines, sentencing regimes, and some people are going to be denied the benefit of later-enacted revisions to the schedule, you know, reducing penalties under the schedule between the time of federal conviction and federal sentencing,” he said.

The other petitioner in the consolidated case, Eugene Jackson, says his 2017 sentencing failed to take into account the federal government’s rescheduling of ioflupane, a cocaine derivative, in 2015.

“All the government says is, well, the schedules are not contained in ACA and so amending the schedules is not the equivalent of amending ACCA,” Jackson’s attorney, Andrew Adler, told the court. But “where one statute incorporates another or cross references another,” he said, “that latter statute is effectively contained and written into the former. That’s how cross-references work.”

When a substance is removed from scheduling, he said, that “it is also removed from ACCA’s coverage.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked at one point in the hearing why the government has an interest in incarcerating people for longer periods of time over conduct that is no longer deemed criminal. “Why would Congress want to incapacitate defendants who have committed crimes that federal law no longer regards as serious?” she said, according to an initial transcript of the oral argument.

The high court’s eventual ruling in the case could impact other criminal defendants facing mandatory minimum sentences for gun possession as the result of past drug crimes.

Shawn Hauser, an attorney who co-chairs cannabis-focused law firm Vicente LLP’s hemp and cannabinoids department, said it’s also an especially relevant issue as the federal government mulls possible rescheduling of marijuana.

“This is fascinating,” she told Marijuana Moment in an email. “And certainly will have potential implications for cannabis offenses in the event of rescheduling.”

In the meantime, the Justice Department has found itself defending federal laws around marijuana and firearms frequently in recent years.

Earlier this month, in a case challenging a government rule against drug users purchasing or owning guns, the government told the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit that historical precedent “comfortably” supports the restriction. Cannabis consumers with guns pose a unique danger to society, the Biden administration claimed, in part because they’re “unlikely” to store their weapon properly before using marijuana.

In a brief submitted in that case, attorneys for the Justice Department argued the firearm ban for marijuana consumers is justified based on historical analogues to restrictions on the mentally ill and habitually drunk that were imposed during the time of the Second Amendment’s ratification in 1791.

The federal government has repeatedly claimed that those analogues, which must be demonstrated to maintain firearm restrictions under a recent Supreme Court ruling, provide clear support for limiting gun rights for cannabis users. But several federal courts have separately deemed the marijuana-related ban unconstitutional, leading DOJ to appeal in several ongoing cases.

The Justice Department asserted similar points during oral arguments in a separate but related case before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit last month. That case focuses on the Second Amendment rights of medical cannabis patients in Florida.

Attorneys in both cases have also touched on a U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruling in Daniels v. United States from August that found the ban preventing people who use marijuana from possessing firearms is unconstitutional, even if they consume cannabis for non-medical reasons.

DOJ had already advised the Eleventh Circuit court that it felt the ruling was “incorrectly decided,” and the department’s attorney reiterated that it’s the government’s belief that “there are some reasons to be uncertain about the foundations” of the appeals court decision.

The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma also ruled in February that the ban prohibiting people who use marijuana from possessing firearms is unconstitutional, with the judge stating that the federal government’s justification for upholding the law is “concerning.”

Also, in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, a judge ruled in April that banning people who use marijuana from possessing firearms is unconstitutional—and it said that the same legal principle also applies to the sale and transfer of guns, too.

In August, meanwhile, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) sent a letter to Arkansas officials saying that the state’s recently enacted law permitting medical cannabis patients to obtain concealed carry gun licenses “creates an unacceptable risk,” and could jeopardize the state’s federally approved alternative firearm licensing policy.

Shortly after Minnesota’s governor signed a legalization bill into law in May, the agency issued a reminder emphasizing that people who use cannabis are barred from possessing and purchases guns and ammunition “until” federal prohibition ends.

In 2020, ATF issued an advisory specifically targeting Michigan that requires gun sellers to conduct federal background checks on all unlicensed gun buyers because it said the state’s cannabis laws had enabled “habitual marijuana users” and other disqualified individuals to obtain firearms illegally.

Meanwhile, attorneys for President Joe Biden’s son Hunter—who has been indicted on a charge of buying a gun in 2018 at a time when he’s disclosed that he was an active user of crack cocaine—have previously cited the court ruling on the unconstitutionality of the federal ban, arguing that it applies to their client’s case as well.

Republican congressional lawmakers have filed two bills so far this session that focus on gun and marijuana policy.

Rep. Brian Mast (R-FL), co-chair of the Congressional Cannabis Caucus, filed legislation in May to protect the Second Amendment rights of people who use marijuana in legal states, allowing them to purchase and possess firearms that they’re currently prohibited from having under federal law.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has committed to attaching that legislation to a bipartisan marijuana banking bill that advanced out of committee last month and it pending floor action.

Meanwhile, Mast is also cosponsoring a separate bill from Rep. Alex Mooney (R-WV) this session that would more narrowly allow medical cannabis patients to purchase and possess firearms.

One place where the matter is particularly relevant is Jersey City, New Jersey, where Mayor Steven M. Fulop (D) is suing over a state policy that allows police officers to use marijuana while off duty.

That challenge, however, has sparked pushback from two police officers, who’ve since sued Jersey City over what they say is a politically motivated move by Fulop in service of a future gubernatorial campaign.

Ohio Republican Lawmaker Files Bill To Allow Cities To Ban Marijuana Use And Home Grow One Week Before Legalization Takes Effect

Read the full article here